Vulnerability of sectors and adaptation to climate change

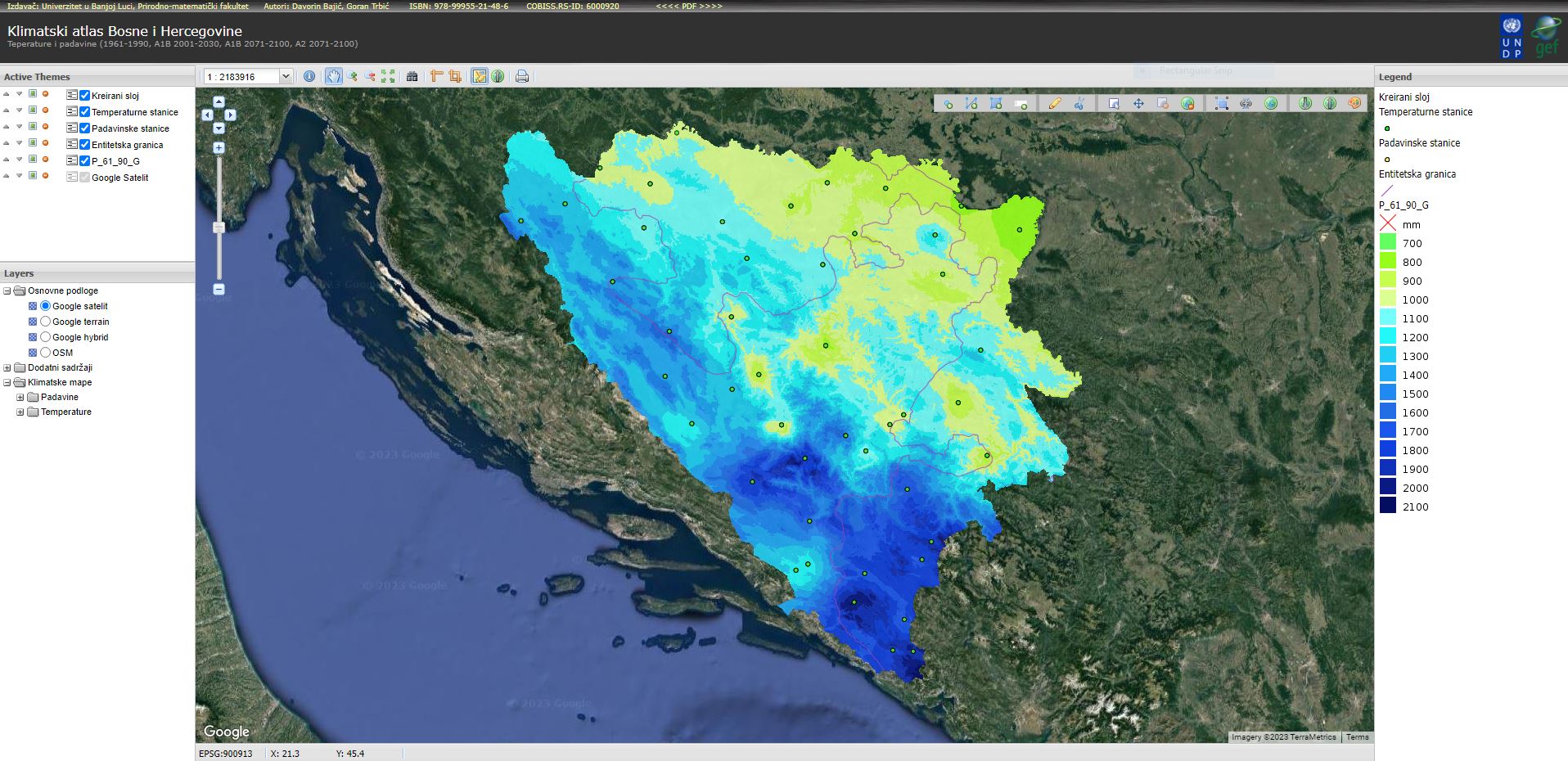

Based on the comparative analysis for the period of 1981-2010, with respect to the reference period of 1961-1990, increases in annual air temperature in the range of 0.4 to 0.8°C were identified, whereas temperature increases during vegetation periods were up to 1.0°C.Significant variability in precipitation has not been noted during the same period, but a decrease in the number of days with rainfall exceeding 1.0 mm and an increase in the number of days with intensive rainfall caused disruptions in the pluviometric regime. Pronounced change in annual rainfall patterns, coupled with temperature increases, are one of the key factors causing more frequent and intensive occurrences of draught and floods on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Over the past several decades, increased climate variability has been noted in all seasons and across the entire territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina: five of the past 12 years were very dry to extremely dry, and four of these years were characterised by extreme flood events. The past four years (2009-2012) have all been characterised by extreme events: flooding in 2009 and 2010, drought and high heat in 2011 and 2012, cold in early 2012, and strong wind in mid-2012.

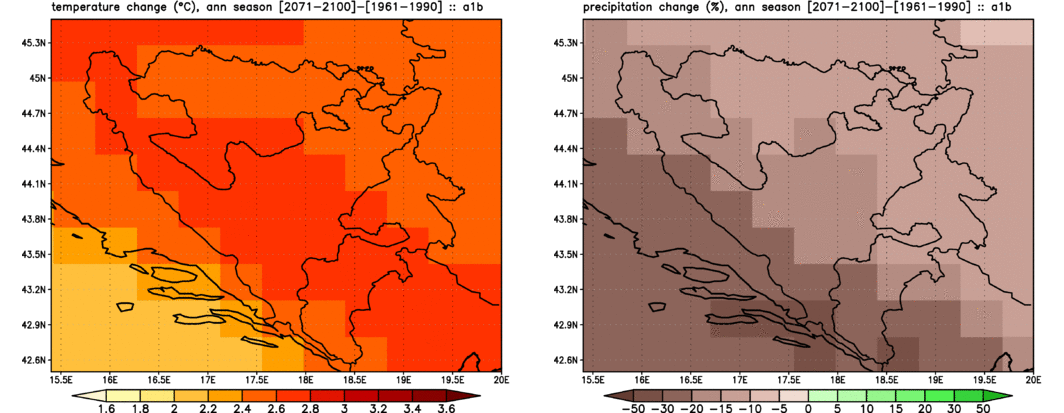

This report presents the results of the coupled regional climate model EBU-POM for future climate change scenarios, obtained by the method of dynamic scaling of results from two global climate models of atmosphere and ocean - SINTEX-G and ECHAM5. We focus on the results from the IPCC SRES scenarios A1B and A2.Model results were analyzed for two intervals: 2001-2030 and 2071-2100. The Communication focuses on changes in two basic meteorological parameters: air temperature at 2m and accumulated precipitation. Changes in these parameters are shown with reference to the mean values from the so-called base (standard) period of 1961-1990.

Results from two global climate models- SINTEX-G and ECHAM5 indicate the mean seasonal temperature increase of average +1°C till 2030, comparing to the base period 1961 – 1990 over the whole Bosnia and Herzegovina. The largest increase of +1.4°C is expected during summer time (June – August). For the A2 scenario (2071-2100), the rapid temperature increase of +4°C yearly average is expected, while the expected increase in temperature during summer time will go up to +4.8°C. Models indicate uneven precipitation changes. Slight increase in precipitation in mountain and central areas is expected, while negative precipitation anomalies are projected for the other areas. According to the A2 scenario for the period 2071-2100, negative precipitations are expected at the whole BiH territory. The largest precipitation deficit of up to 50% comparing to the base period 1961-1990 is expected during summer time.

Sectors that are most vulnerable to climate change in Bosnia and Herzegovina are as follows: agriculture, water resources, human health, forestry and biodiversity, as well as the vulnerable ecosystems. Detailed analyses were conducted of long-term climate change vulnerability and impacts in these sectors based on the SRES climate scenarios A1B and A2 discussed above.

In agriculture, climate change impacts include reduced yields as a result of reduced rainfall and increased evaporation; a potential decrease in livestock productivity; increased incidence of agricultural pests and crop disease; and increased food insecurity. Potential positive impacts include an extended growing season and greater potential for growing Mediterranean crops in Herzegovina. In water management, climate change impacts include more frequent droughts (in Western BiH), a reduction in summer river flows and more frequent floods. In the health sector, potential negative impacts include an increase in the frequency and magnitude of epidemics/pandemics due to warmer winters; increased mortality due to heat waves; the possible spread of the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedesalbopictus); and an increase in tick-borne diseases (Lyme borelliosis and tick-borne encephalitis). Potential positive impacts could include cold-related deaths. In the forestry sector, potential negative impacts include increased frequency and extent of forest fires; increased risks to rare and endangered forest communities; increased bark beetles and gypsy moths (North Atlantic oscillation [NAO] index); and a risk of the transformation of forest ecosystems, resulting in large-scale tree mortality. Potential positive impacts include faster growth rates and the emergence of new species with economic potential. In the area of biodiversity and sensitive ecosystems, potential negative impacts include the loss of existing habitats; habitat fragmentation; species extinction; rapid temperature and/or precipitation changes, affecting ecosystem functions. Potential positive impacts in the sector include the emergency of new habitats.

In agriculture, adaptive capacity to climate change is low. There is a lack of crop modelling and a lack of climate data necessary for Early Warning Systems. Farmers need to be trained in less labor-intensive methods of cultivation, and they lack knowledge about hail protection techniques. Farm equipment is often obsolete, and there is a lack of rainwater collection. Finally, climate issues are not mainstreamed into sectoral policies on agriculture. In the water sector, there is a critical lack of hydrological modelling and detailed vulnerability assessments, maps, and risk charts. There is a lack of investment in water supply systems, resulting in high levels of leaks and losses. There is a lack of flood protection measures, and more generally, climate change issues are not integrated into water sector policies and programs. In the health sector, adaptive capacity is constrained by a lack of acute and chronic disease monitoring. There is low awareness among health care providers and their patients about climate-health linkages. There is a lack of financing for health-related adaptation measures, and difficulties in accessing primary care in rural regions do not allow health care providers and public health authorities to manage potential climate-sensitive chronic and infectious diseases. Adaptive capacity to climate change in the forestry sector is very low. The most vulnerable regions have not been defined. There is no detailed analysis on how climate change affects forest systems and communities. Fire protection technique is obsolete and insufficient. As in the other sectors, there is a lack of integration of climate change issues into sectoral policies and strategies. Although some of the species have already been affected by temperature increase and precipitation decrease, the most vulnerable areas and flora and fauna species have not been defined, which reduces adaptive capacity in biodiversity and sensitive ecosystems. For each sector, proposed adaptation measures were identified using expert consensus, stakeholder consultation, and a review of relevant research.